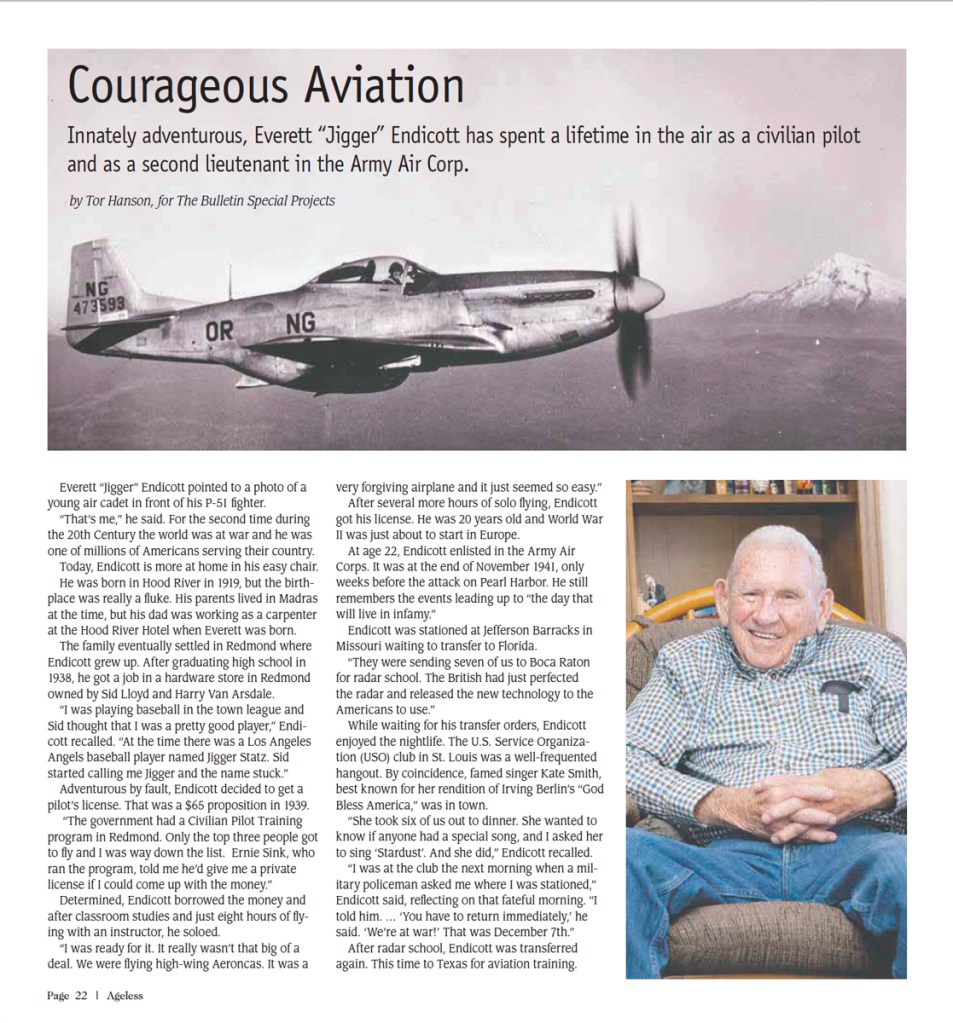

“Jigger” Endicott in a P-51 Mustang. Photo courtesy of the Endicott family.

Originally published in Ageless Magazine – Winter 2015

Innately adventurous, Everett “Jigger” Endicott has spent a lifetime in the air as a civilian pilot and as a second lieutenant in the Army Air Corp.

Everett “Jigger” Endicott pointed to a photo of a young air cadet in front of his P-51 fighter.

“That’s me,” he said. For the second time during the 20th Century the world was at war and he was one of millions of Americans serving their country.

Today, Endicott is more at home in his easy chair.

He was born in Hood River in 1919, but the birth- place was really a fluke. His parents lived in Madras at the time, but his dad was working as a carpenter at the Hood River Hotel when Everett was born.

The family eventually settled in Redmond where Endicott grew up. After graduating high school in 1938, he got a job in a hardware store in Redmond owned by Sid Lloyd and Harry Van Arsdale.

“I was playing baseball in the town league and Sid thought that I was a pretty good player,” Endicott recalled. “At the time there was a Los Angeles Angels baseball player named Jigger Statz. Sid started calling me Jigger and the name stuck.”

Adventurous by fault, Endicott decided to get a pilot’s license. That was a $65 proposition in 1939.

“The government had a Civilian Pilot Training program in Redmond. Only the top three people got to fly and I was way down the list. Ernie Sink, who ran the program, told me he’d give me a private license if I could come up with the money.”

Determined, Endicott borrowed the money and after classroom studies and just eight hours of flying with an instructor, he soloed.

“I was ready for it. It really wasn’t that big of a deal. We were flying high-wing Aeroncas. It was a very forgiving airplane and it just seemed so easy.”

After several more hours of solo flying, Endicott got his license. He was 20 years old and World War II was just about to start in Europe.

At age 22, Endicott enlisted in the Army AirCorps. It was at the end of November 1941, only weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor. He still remembers the events leading up to “the day that will live in infamy.”

Endicott was stationed at Jefferson Barracks in Missouri waiting to transfer to Florida. “They were sending seven of us to Boca Raton for radar school. The British had just perfected the radar and eleased the new technology to the Americans to use.”

While waiting for his transfer orders, Endicott enjoyed the nightlife. The U.S. Service Organization (USO) club in St. Louis was a well-frequented hangout. By coincidence, famed singer Kate Smith, best known for her rendition of Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America,” was in town.

“She took six of us out to dinner. She wanted to know if anyone had a special song, and I asked her to sing ‘Stardust’. And she did,” Endicott recalled.

“I was at the club the next morning when a military policeman asked me where I was stationed,” Endicott said, reflecting on that fateful morning.

“I told him. … ‘You have to return immediately,’ he said. ‘We’re at war!’ That was December 7th.”

After radar school, Endicott was transferred again. This time to Texas for aviation training. His time as an aviation cadet in Texas was a fortuitous event. He met his future bride, Betty, at the USO Halloween dance in San Antonio in 1942.

“They lined up the girls on one side of the club and the cadets on the other side,” Endicott recalled. “Betty pointed her finger at me, came over and we started to dance.”

That dance changed the course of their future. The two began dating and on July 23, 1943, they tied the knot. It was a “parade day” for Endicott. He got his pilot’s wings, got his commission as second lieutenant in the Army Air Corp, and married Betty.“

She was the loveliest, nicest girl that I had ever met! And she hasn’t changed.”

After receiving his wings, Endicott put in a request to fly single-engine airplanes. That meant flying fighters. He was sent back to Florida for additional training before he was scheduled to go overseas to join the war.

But fate intervened. While the rest of his class was sent overseas, Endicott was told to stay behind as a flight instructor.

“I went to see the commander. I told him that I wanted to go overseas with the rest of the guys. He told me point blank, ‘No one asked you what you want to do.’”

Recognizing that a lieutenant should never argue with his superior officer, Endicott said, “Yes, sir!”

As an instructor, Endicott flew the latest breed of high-performance warplanes, teaching cadets how to fly the P-40 “Warhawk” and the P-51 “Mustang.”

While some flight instructors were known for pulling rank and yelling at their cadets, Endicott said he had a more fair and understanding approach.

There were no two-seat trainers at the time, so Endicott had to fly beside his students and talk them through how to fly the airplanes.

Endicott especially liked the “dogfight” training.

“I guess I was a bit more aggressive. I liked beating the other guy. That’s why they kept me as an instructor.”

When he returned to civilian life after the war, Endicott went back to his pre-war job at U.S. Bank. But a life in the air was tough to give up. Endicott got a job as a crop-duster for Cal Butler. It was a different type of air acrobatics.

“At the time, we didn’t have any equipment to see what we had already sprayed. We flew low enough to make wheel marks on the potato vines so we could see where we had been,” Endicott said.

“I was doing pretty well until I tried to cut down a juniper tree in Prineville.”

Endicott lost the duel with the tree and ended up in the hospital for a week.

In 1953, the Air Force called and wanted him back. This time he got to teach cadets to fly jets – the T-33 “T-Bird,” F-80 “Shooting Star,” and F-84 “Thunderflash” and “Thunderstreak.”

“Jets were easier to fly because you had no torque,” Endicott explained.

A pilot has to take the torque in consideration when he’s flying a propeller airplane. The plane wants to turn itself around the axis of the propeller.

“A P-51 had so much torque that you had to use the right break until you got up to a certain speed. There were no such issues flying jets.”

Endicott’s flying days came to a halt when the doctor told him he had a heart murmur. He may have been grounded, but Endicott still wasn’t done with airplanes. He was transferred to Strategic Air Command as an aircraft maintenance job control officer. In that position, the former pilot even got to take a small part in the Cuban Missile Crisis.

After the U-2 spy planes took pictures of the missile sites in Cuba, the films were sent to Westover where Endicott was stationed.

“We had a plane ready to fly to Kodak Eastman headquarters in Rochester, New York to have the films developed.”

After an assignment in Burma as an aircraft maintenance advisor for the Burma Air Force and a tour in Vietnam, Endicott retired in 1969 as a lieutenant colonel with a Bronze Star for meritorious service.

“Jigger” Endicott still lives in Redmond with his wife Betty. They have been married for more than 72 years and have raised two kids. Their son George is the mayor of Redmond and daughter Carol lives in Massachusetts.

A life well lived, sums up Endicott’s experiences. When it comes to picking his favorite episode, Endicott pauses.

“There are so many doggone good memories. It’s difficult to pick out just one single moment.”

“Ask him about his Honor Flight,” his daughter, Carol, whispered. Overhearing her, Endicott cracked a smile.

Once a year, Bend Heroes Foundation flies veterans free of charge to see the World War II monument and other places of remembrance in Washington D.C.

“I got to lay down a wreath a the ‘Tomb of the Unknowns’ at the Arlington Cemetery,” Endicott shared. “It’s the greatest honor that I have ever had.”